In this piece, we present a map and vocabulary to navigate the decentralized infrastructure of Pocket Network. After skimming, you’ll have a clear picture of the puzzle pieces that fit together to make Pocket Network efficient, resilient, and fruitful for its participants. You’ll learn about each role, see how it may apply to you or your project with Pocket Network ecosystem, and get a clear next step to better building, operating, or funding your endeavors.

Even to skilled technologists, entering the Web3 world can be confusing. Consider a core, modern building block of software engineering, the API. In Web3, an API doesn’t exist without a node and a provider – but what do these terms mean?

An application targets something (an API name), someone is accountable for serving it, and some machine actually produces bytes. Let’s understand how they come together to a greater whole.

This post separates these components into 3 parts —Service, Source, Supplier—and illustrates how they appear in the decentralized web stack most teams use today, namely: via Gateways through PATH, routing/proofs, and on-chain receipts. For production docs and hands-on steps, you’ll see pointers to the official guides throughout.

Reliable access to public data only works when responsibilities are explicit. Pocket Network organizes its access layer around three roles that work together every time a request moves through the system:

- a Service – in the form of a frontend interface or dApp

- a Source – acting as the backend

- and a Supplier – in the form of the staked operator

Keeping those roles distinct is what turns “API calls” into something you can reason about operationally and economically.

As we dig in, you’ll see how Services are registered and versioned, how Sources are declared with measurable capabilities, and how Suppliers attach those Sources to Services and earn only for verified work.

Two outer forces—Stake (for alignment) and Settlement (receipts and payouts)—close the loop. The result is a data layer where correctness, performance, and cost are observable rather than assumed.

Whether you’re building, operating, or funding, the goal here is practical literacy. By the end, you should know exactly what to point your app at, what to declare and monitor if you run infrastructure, and what to measure if you track outcomes, so decisions are made on evidence, not slogans.

Service

A Service is a public declaration that specifies the type of data an application needs, the delivery requirements, and the quality standards it must meet. It acts as a registered request for any Supplier that can fulfill these criteria, enabling applications to access data through defined APIs rather than directly through nodes.

When you hear “Service” in relation to Pocket Network, think of it as a public broadcast that tells the network what kind of data an application wants, how it should be delivered, and what quality bar it must meet. This is done via a named contract, at the access layer – NOT via a server.

A Service is neither a URL nor a node. It is the declared API target that your app calls, acting as a registered request: “any Supplier who can meet these rules may answer this request!”

If you’ve ever called eth-mainnet-archive or token-transfers-v1 through a Gateway, you’ve already used a Service. Under this label is the full scope of your workload: the API surface (eth_* methods), the data depth (archival), and the performance expectations.

Behind it, multiple Suppliers register Sources that satisfy that contract.

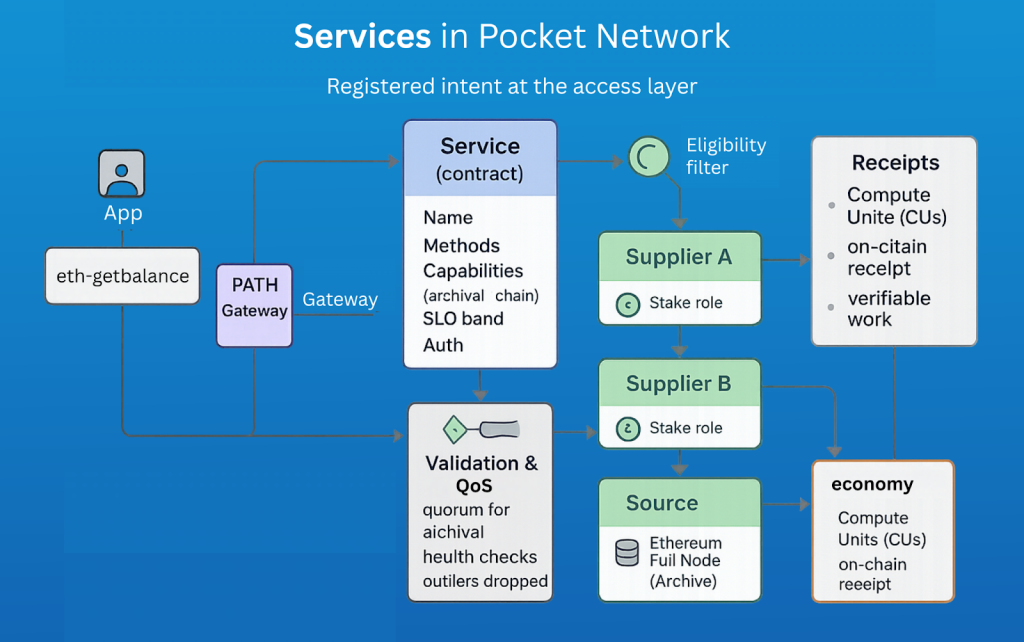

Service in Pocket Network Stack

How a Service behaves in the Shannon/PATH stack

In Shannon’s architecture, every Service definition lives in the registry layer of the access stack—think of it as the network’s menu of available data offerings. The PATH Gateway reads this registry, validates the descriptors, and exposes them to clients as stable targets. When a request comes in, the Gateway knows exactly which Suppliers and Sources qualify to serve it.

- Your app calls the Service by name, e.g., eth_sep_test, sentence-similarity, zksync_era, etc.

- The Gateway looks up the Service descriptor, filters to eligible Suppliers (e.g., only those that declared archival Sources if archival is required).

- The request is routed to a healthy, fast Source behind an eligible Supplier.

- If the Service requires additional checks (e.g., deep-history reads), the stack validates the results before returning them.

- A short receipt is logged to account for usage later.

For more information on setting up a Service in Pocket Network, please refer to the documentation here and here.

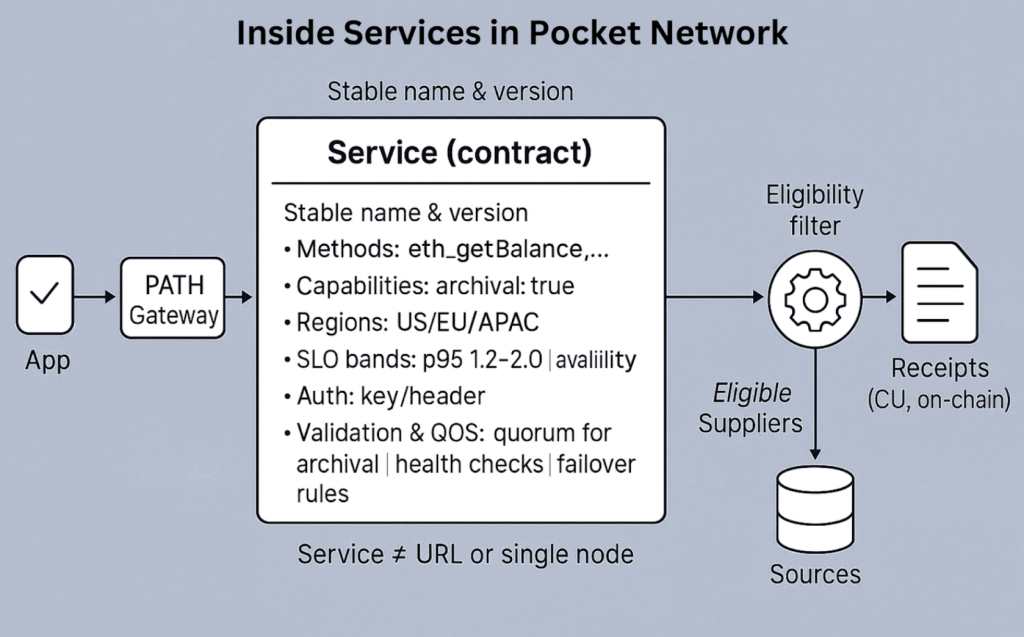

Service Explained inside Pocket Network Data Architecture

What defines a Service in Shannon

Each Service descriptor includes:

- Identifier (name and version): A globally unique name or a stable label apps hit (versioned when you change behavior, not when you swap machines). Examples include eth-mainnet-archive, btc-indexer, llm-inference-v1, etc.

- Protocol type: RPC, REST, GraphQL, or a custom endpoint style that this Service promises to support.

- Quality/Capability flags – archival requirements, max latency, minimum availability, network/chain IDs, data freshness expectations.

- Schema/version – to avoid silent changes.

- Policy hints: preferred regions/latency bands, error-mapping behavior, and optional validation rules.

- Auth posture: how callers identify themselves (keys, headers) at the Gateway.

- Ops notes: short SLO bands (e.g., “p95 typically 1.2–2.0s”), maintenance windows, and deprecation dates.

- Governance linkage – who can update the descriptor and under what vote type.

Think of this as a short descriptor that the Gateway can read to determine which responses are valid and which operators are eligible to serve them. For more information, check the Service FAQ documentation.

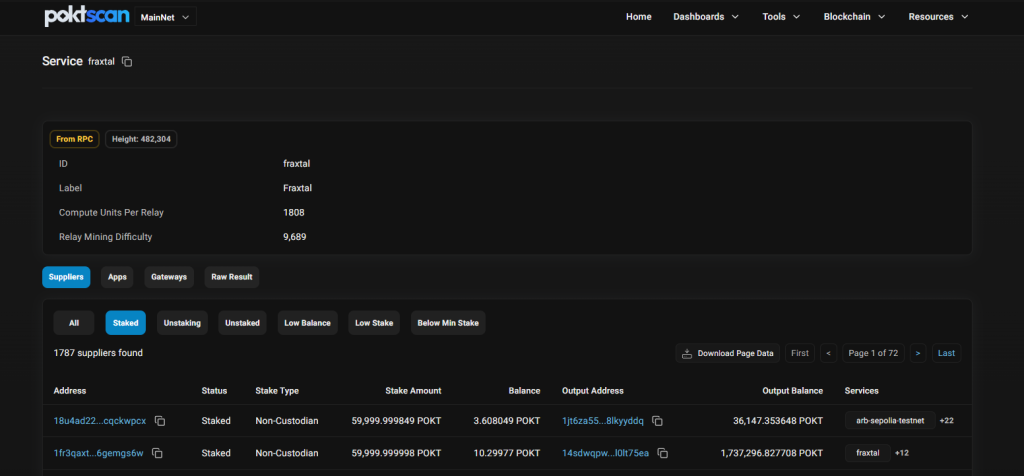

Services ranked by compute units over the last 24 hours. Source: POKTScan

Service examples and scenarios

Example 1: Getting an RPC Archive data using eth-mainnet-archive

When an application like a block explorer calls the eth-mainnet-archive Service for eth_getBalance at block 13,000,000:

- PATH recognises that this Service requires archival data.

- It queries the network’s supplier registry for eligible Suppliers—those who have declared archival-capable Sources.

- It routes the request to one or more healthy Sources from that list.

- It validates responses (via RelayMiner) to confirm that the data truly originated from the required archival height.

- Once validated, the request produces a receipt, which is later settled on-chain as Compute Units (CUs).

So, “Service” here serves as the governing contract between the application and the network’s supply layer; it decides who can answer, how proof is generated, and what counts as valid work.

Why Services matter to Pocket’s economics

Shannon’s mint=burn model only works because Services are standardized. Every relay or inference request passes through a Service definition that determines:

- How much a Compute Unit costs, and

- What qualifies as valid work to mint corresponding rewards?

Without that clarity, you’d have chaos; different Suppliers defining “good enough” differently, and no way to verify usage on-chain.

Real Examples of Services on Pocket Network

| Service label | What it is | POKTScan Links |

| text-generation | LLM inference endpoint exposed via PATH (OpenAI-style access). | link |

| fuse | Fuse Network RPC (EVM). | link |

| zksync_era | zkSync Era RPC (ZK rollup, EVM-compatible). | link |

| poly-zkevm | Polygon zkEVM RPC (EVM, ZK rollup). | link |

| bsc | BNB Smart Chain RPC (EVM). | link |

Next, we’ll look at the Source—the infrastructure behind the scenes that turns these contracts into actual data —and how Shannon formalizes its role in routing, validation, and reliability.

Source

A Source refers to the actual machine or node that produces and delivers the requested data. It registers with Suppliers to fulfill the contract defined by a Service, ensuring it meets the quality and performance standards set forth in the Service descriptor.

If a Service is the promise, a Source is the machine that keeps that promise. It’s the real system—full node, indexer, or model server—that actually produces the bytes an app receives.

More specifically, in Pocket Network, especially under Shannon, a Source isn’t just a computer buzzing somewhere; it’s a declared, observable capability. It carries measurable properties, health signals, and eligibility status that the protocol uses to decide who gets to serve and who sits out.

Sources are replaceable: you can add them, rotate them, or remove them from eligibility without changing which apps point to them (that’s the Service’s job).

Characteristics of Sources

- It’s a runnable thing with an address (node, process, model server).

- It has measurable properties (depth, freshness, latency, error behavior).

- It is owned/declared by a Supplier, but the Source itself is not “the role.”

The Source in Context

Every Supplier registers one or more Sources to serve specific Services. Think of it like this:

“A Supplier says, “I can serve the eth-mainnet-archive Service,” and declares two Sources—one archive node in US-West, one in EU-Central.

The Gateway sees these Sources, tracks their health, and uses them when routing requests that match that Service’s descriptor.”

So while the Service defines what needs to be served, the Source defines how and from where it’s actually delivered.

What Makes a Source

Each declared Source has a few key fields, such as its identity, capabilities, and status, that are constantly tracked by the network.

| Category | Example | Why It Matters |

| Type | EVM full node, REST indexer, model endpoint | Defines what kind of data it can serve |

| Capabilities | archival: true/freshness <2 blocks | Filters eligibility for certain Services |

| Region | us-west/eu-central | Helps route requests by latency |

| Performance stats | avg latency, error rate | Drives routing priority |

| Status | healthy/cooling/disqualified | Decides whether traffic gets routed |

Additional specific fields that define a Source, which PATH Gateways and Apps monitor, include:

- Archival depth: how far back it can answer truthfully.

- Freshness/lag: how close it is to head; how it behaves during reorgs.

- Consistency: whether it agrees with peers on sensitive reads.

- Latency shape: not just averages; watch p95/p99 tails.

- Capacity: sustained throughput before tail latency blows out

- Error taxonomy: does it fail with clear codes, or just time out?

How Pocket treats Sources (Shannon-era behaviour)

- Eligibility is conditional. A Source is eligible for a given Service only if it matches the Service’s flags (e.g., archival required) and passes health checks.

- Validation can protect correctness. For deep-history reads or other sensitive paths, the stack can cross-check multiple archival Sources and ignore outliers before returning a result.

- Rotation is normal. Sick Sources are dropped from eligibility; they can re-enter after passing checks over a cooling window.

- Observability is first-class. You can see which Sources were eligible, selected, or disqualified, and how they performed over time.

Real Examples of Sources on Pocket Network

POKTscan exposes Services and Suppliers as first-class pages, but it does not publish per-Source views; To actually see your Sources named, you’ll need your own PATH/WATCH setup, or check the Gateway/WATCH health-check dashboards, which list the declared Sources being sampled; there isn’t a public per-Source listing.

To enhance understanding, please refer to a brief illustrative example of a typical Source profile. You don’t have to publish a YAML like this, but it helps to think of every Source as having a capability card that the network can reason about.

source_id: supplier-12/us-west/eth-archive-03

serves: [eth-mainnet-archive]

archival: true

freshness_target: head_lag <= 2 block

slatency_bands:

p95_ms: 1200-2000

validation:

deep_history_quorum: enabled

outlier_backoff: 30m cool-off on mismatch

region: us-west

notes: prefers block ranges; heavy state_diff calls may spike tailSource examples and scenarios

Scenario A: Blockchain RPC (archive depth)

You query eth_getBalance at block 10,000,000 through eth-mainnet-archive.

- The Service requires archival data.

- The Gateway filters to Sources that have archival:true set.

- Two Suppliers qualify; one Source fails the height check (it’s missing older blocks) and is disqualified temporarily.

- The other returns the result; the Gateway logs a valid CU receipt.

The Source serves as the measurable backend, where eligibility and proof determine who gets to provide Services, rather than relying on brand names or uptime promises.

Scenario B: Model inference (AI endpoints)

You use an LLM Service (llm/llama3-chat) to call chat completion with ~6K prompt tokens.

- Each Source (model server) publishes its context window and latency bands.

- PATH routes requests to the Source that can handle the token size and stay under the SLA.

- The slowest Source is automatically throttled; once stabilised, it re-enters rotation.

Intricacies of Sources in Pocket Network Data Layer

Supplier

If the Service is the contract and the Source is the engine, then the Supplier is the operator who keeps everything running and accountable.

A Supplier is the staked participant responsible for exposing one or more Sources to serve specific Services. In Pocket, Suppliers are not abstract; they’re on-chain actors with measurable performance, QoS obligations, and clear economic ties.

They’re the people or teams who say,

“We’re willing to serve this Service, using these Sources, under these conditions—and we’ll stake POKT to prove we mean it.”

The Supplier Architecture in Pocket Network

Suppliers live between the Eligibility layer and Proof/Settlement layer in the data path:

App → PATH Gateway → Service → Eligibility → Supplier → Source → RelayMiner → QoS and Settlement

When a request hits the network, the Supplier’s job is to:

- Expose Sources that match the Service’s descriptor (archival, freshness, region).

- Maintain health and quality across those Sources to stay eligible.

- Serve verified traffic that produces receipts and eventually earns payouts..

What a Supplier Actually Does

A Supplier’s day-to-day role in Pocket Network looks less like “running a node” and more like “running a service business under protocol rules.”

Here’s what that means:

- Declare Sources: The Supplier registers each Source they control, linking it to one or more Services. For example, one Supplier might run two archival nodes for eth-mainnet-archive and a REST indexer for token-transfers-v1.

- Stay eligible. Keep Sources inside the Service’s capability envelope; if one drifts or lags, it’s cooled or disqualified until it recovers.

- Compete on evidence. Selection weight is earned through correctness and tail latency, not marketing.

- Plan capacity. Add or remove Sources to meet demand in the regions that matter for that Service.

- Operate with receipts in mind. Everything served is tied to a proof; eligible vs. earned becomes a clear number, not a debate.

- Manage stake: The Supplier’s POKT stake is their bond, too little, and they can’t serve high volume; misbehavior can lead to penalties or slashing.

For further details on how to become a Supplier in Pocket Network, please refer to the documentation guide available here.

Real Examples of Suppliers on Pocket Network

| Supplier (address) | What to use this page for | POKTScan Link |

| pokt15pp2…enr80 | See which Services this Supplier serves, eligibility/uptime patterns. | link |

| pokt1rph7…09z6 | Drill into performance per Service; compare against peers. | link |

| pokt1yd6k…sy2y | Check regions/Sources attached to each Service. | link |

| pokt18u4a…pcx | Verify eligibility vs. earned over recent windows. | link |

| pokt1c33v…ptkm | Cross-check which Services this Supplier focuses on. | link |

Supplier’s economic role in Pocket Network

Under Shannon, economics revolves around verified work. A Supplier’s income depends on how much validated traffic they serve, not how long their nodes were online.

Here’s the loop

- The Supplier’s stake defines their capacity and eligibility.

- Every verified request burns POKT (on the user side) and mints POKT (on the supply side) under the mint=burn model, keeping token economics balanced.

- The Supplier earns a portion of the minted tokens proportional to the number of their validated CUs.

- Governance adjusts only one parameter —the Compute Unit Target Token Multiplier (CUTTM) —to keep costs predictable in fiat terms.

So, when the network grows, Suppliers don’t get paid by inflation—they get paid for proof of performance.

List of Suppliers for the Fraxal data Service on Pocket Network. Source: POKTScan

Accountability and Reputation

Suppliers are tracked by measurable, on-chain stats, including:

- Eligibility rate: how often they’re qualified to serve.

- Correctness rate: how often their results pass quorum.

- Latency percentile: their median and tail response times.

- CU share: how much traffic they serve across all Suppliers.

These metrics are visible through explorers and dashboards. This transparency makes every Supplier’s reputation public, a core principle of Shannon’s design.

Supplier scenarios and examples

Scenario A: The Archival Duo

Two Suppliers both serve eth-mainnet-archive. Supplier A’s Sources respond faster, but are in a single region. Supplier B’s Sources are slightly slower but have more exhaustive coverage. PATH balances requests dynamically, where the fastest wins short bursts, and the wider one fills global gaps. Both Suppliers stay profitable because correctness and latency determine routing, not favoritism.

Scenario B: The Indexer Expansion

A Supplier running a REST indexer decides to scale. They add two more Sources in new regions, re-run health sampling, and watch their traffic double. Their stake and reliability grow together, while the network automatically trusts what it can measure.

The Surrounding S’s — Stake and Settlement

The 3S model —Service, Source, Supplier —only works because two other forces hold it together: Stake and Settlement. They’re not extra roles, just the guardrails that turn technical reliability into economic truth.

Stake is the commitment layer. Every Supplier locks up at least 15,000 POKT to become eligible to serve a Service and keep their Sources within spec, such as archival, freshness, latency, and correctness.

That stake isn’t symbolic; it’s the signal that the network can trust your performance. If a Supplier’s Sources drift or fail quality checks, they’re automatically cooled or penalized. In a nutshell, Stake aligns incentives so that reliability isn’t voluntary; it’s enforced.

“For instructions on setting up and configuring a supplier staking configuration required to submit a stake transaction, please refer to our documentation here.”

Settlement is where proof becomes payout. Every validated relay and every byte served through a healthy Source under a registered Service becomes a Compute Unit (CU). Those CUs flow through the mint-burn economy introduced in Shannon, where token supply expands and contracts with real usage. Verified work earns; failed or invalid work doesn’t.

Together, Stake and Settlement close the loop on Pocket’s data layer. They make performance measurable, reward verifiable work, and keep the network’s economics tied to what actually happens on-chain.

The Next Step — Building on Verified Data

Everything we’ve explored—the Services that define intent, the Sources that produce truth, the Suppliers that stand accountable, and the Stake and Settlement that keep it all honest—exists for one reason: to make data verifiable, valuable, and open to everyone who builds with it.

Pocket Network isn’t just a relay network; it’s a living system for data integrity. Every proof, every receipt, every relay represents a measurable step toward a world where infrastructure and economics speak the same language: evidence. That’s why this model isn’t theoretical—it’s an open invitation.

- If you build, explore a Service, and test its quality signals.

- If you operate, become a Supplier, and measure your performance against the network’s proof layer.

- If you fund, track how verified work converts into growth, not noise.

The data has always spoken for itself. Pocket just makes sure it can be heard, trusted, and rewarded.

You can read our developers’ guide blog, written specifically for developers building on Pocket Network after the Shannon upgrade.

Closing thought

It’s tempting to treat “the network” as a single blob and “RPC” as a single thing. But your app doesn’t hit “the network.” It hits a Service, which is served by a Supplier, using one or more Sources. Once you think this way:

- Incidents aren’t mysterious—they’re localized and fixable.

- Costs aren’t vibes—they’re proved, priced, and auditable.

- Growth isn’t hype—it’s Services added, Suppliers competing, and receipts you can count.

Keep the 3S straight. Keep Stake and Settlement in view, but at the edge. And keep your hands on the artifacts—descriptors, validations, receipts—because that’s where alignment happens.